by AbdouMaliq Simone

Goldsmiths College, University of London

Appreciating the unintelligible

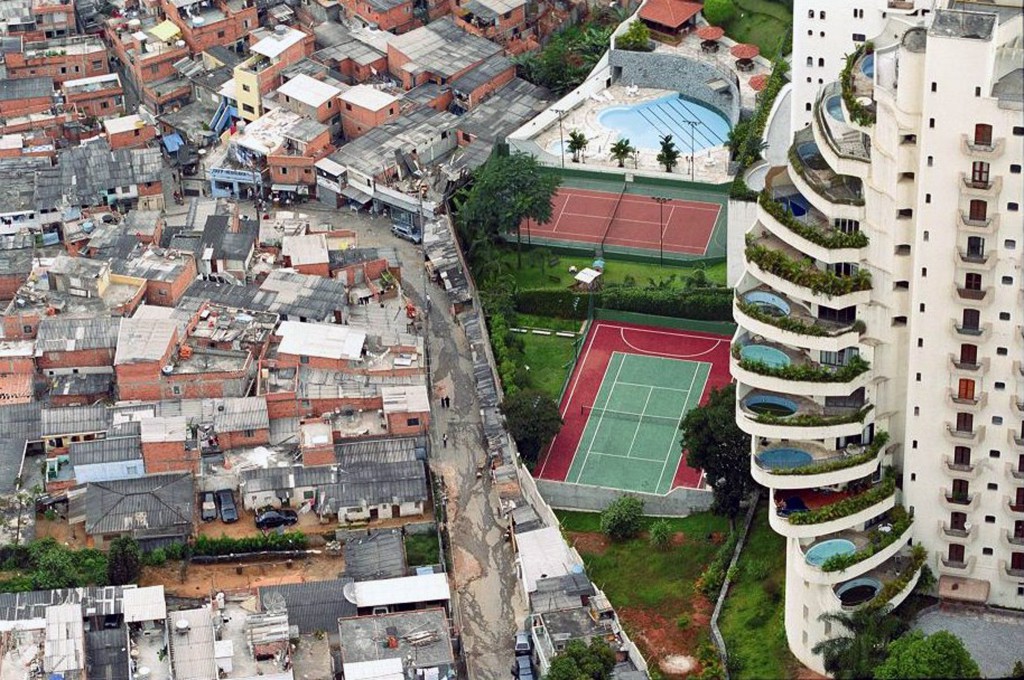

If the experiences of cities and urban regions across a diffuse and often conceptually murky Global South are to exert a critical effect on urban theory in general, a wide range of seemingly “missing” people, spaces, and practices must be considered. In large metropolitan regions like Sao Paolo, Karachi, Delhi and Jakarta specifically, the lives and terrain of a possible “majority”—straddling and making ambiguous the distinctions among “upper poor,” “working class,” and “lower middle class” –barely register in discussions of the probable and potential futures of cities. While this designation of the “majority” is intentionally provocative and heuristic, these residents may indeed make up the bulk of the population in many metropolitan regions of the Global South.

This disappearance is not simply attributable to conceptual omissions or an occlusion that stems from an inherently unstable and excessively heterogeneous population. For the political richness of such a purported disappearance entails all of the ways in which such residents have been complicit in bringing it about. For the poor and for the middle class there have been either obvious advantages or administrative exigencies at work in making them visible. Most claims for rights and services for the poor depended upon making their presence an inevitable and significant aspect of a city’s development, usually in face of an imposed scrutiny seeking to blame them for all that was wrong about the city. By contrast, transparency in the case of the middle class was a critical platform on which to situate their claims of eligibility—the “normative citizen”—and to steer the city to meet their needs for the clear accountability of property rights, individuated consumption, and political authority that demonstrated their entrepreneurial capacity and commitment to “doing the right thing.”

For the “majority,” it was important to construct built environments that facilitated mutual witnessing as a form of continuous renovation of the narratives of economic well-being and social coherence. In other words, opportunities for residents to pay attention to each other were not created in order to ensure that their behaviors conformed to the prevailing standards of propriety and efficacy. Rather, this witnessing was the very condition to continuously remake what those standards looked like and as a means to redraw the lines of social collaboration—i.e., folding residents into new constellations of collective action that need not be stabilized in particular forms over time. On the other hand, as such continuous mutability did not obviate the ways in which residents continued to associate with particular structures of belonging—kinship networks, ethnicity, histories of origin, occupational grouping—their subjection within the various tools that government applied in order to read their lives meant that these associations were taken to “stand in” for the entirety of their social economies.

Even in today’s variegated neoliberal urban conditions, probabilities, accountancy, and the stochastic modeling of risk are the things that really matter. This is not only because they are the instruments that work with large assemblages of data and uncertainty to specify the positions, the hedges, and the arbitrage that are critical for any urban economy, but also because they are the seemingly proficient instruments of dissimulation. They cover up for the fact that no one knows quite what is going on. This efficacy is derived from the way they make everything count, everything accountable; the ways in which large volumes of raw data can be scrutinized in order to establish the visibilities, the patterns that are worthy of being discerned, that will constitute the locus of intervention. Everything else that falls outside of such modeling does not matter. For large numbers of residents in cities of the majority world, then, the dilemma is how to demonstrate that where they live and what they do matters, when the possibilities of translation, visibility, and value become more problematic. On the other hand, it is important, and to a large extent has been important for a long time, to stay outside the count, to not get sucked into the game of who and what is eligible and who is not.

If an intensified emphasis on the urbanized experiences of the Global South is going to matter, then the specific histories, practices and conditions of this “urban majority” have to be situated in an analysis appreciative of the tricky and unfinished cat and mouse game of coloniality. We must keep in mind that in the postcolonial world, the onus of constructing viable built environments and urban economies was placed largely on the “majority” itself—through well-known processes of auto-construction. The very concretization, then, of the possibility of citizenship, depended upon the densification of techniques—the intermixing of measures, angles, calculations, impulses, hinges, screens, surfaces, soundscapes, exposures, folds, circuitries, layers, tears, inversions as instruments for associating things, bringing things into association, where things get their “bearings” by having a “bearing” on each other.

Urban authorities often tried to limit the growth of urban populations or defer the affordance of rights to exist in cities. Still, they faced the necessity of managing the city’s inhabitants according to specific conditions that made the actions, intentions, and aspirations of these inhabitants visible in terms of the fact that the responsibilities and claims were those of individuated persons or households. The technique of citizenship—that in which every inhabitant is accorded rights and responsibilities as an individual regardless of their status or history—was often applied as a form of management without political substance. Individuals were to be enclosed, self-sufficient entities. In part, this derived from recognition of the intrinsic volatility of urban life, its tendencies to fracture and separate. Collective formations then were to be the aggregation of individuals, who would functionally work out divisions of labor, roles, and hierarchies of authority. But this circumscribed concept of collective life made little provision for processes of imitation and contagion—the ways in which urban life engenders fascinations, curiosities, affective intensities, and proliferating intersections of “fugitive materials”—gestures, sounds, phrases, and ways of doing things unmoored from any particular sense or eligibility.

As such, the value and trajectory of effort embodied by these “nebulous” spaces and populations cannot be assessed simply within the predominant terms of urban productivity, citizenship, rights, individuation, public, private, or civil action. If such terms point to a range of specific devices that are applied in order to render actions legible and intelligible, and if intelligibility is an objective of governing, of deciding what is real and what is not, then the elaboration of the “unintelligible” becomes an important method of creating spaces of operation (as Justin Read suggests). This is not the metaphysics of “undecideability.” Rather, it is a politics of slowing things down, of instantiating possibilities to keep things open, even if it means showing back to hegemonic actors aspects of the practices that are acknowledged as playing a critical role in the reproduction of that hegemony.

This practice may constitute an implicit acknowledgement by the weak of the capacities of the strong. They may signal that, in the hands of the weak, these practices can never be implemented in ways sufficient to challenge the strong. The very same kinds of practices that in the hands of those with powers are construed as calculating, daring, and innovative, in other hands are seen as impetuous and self-destructive. These are the very behaviors, then, which would seem to disqualify “ordinary residents” from being eligible to participate fully in a wide range of managerial, decision-making processes. Yet, in this process of mirroring, limited spaces of maneuverability are opened and for much of the very same reasons they are opened for those supposedly much more well-versed in using them. In the process, residents elaborate an urban environment whose reverberations of diverse, intersecting matters—agendas, concerns, activities, calculations, affective intensities, and compositions—make it difficult for any single set of actors to unilaterally restructure the textures and uses of that environment. Whether property developers, municipal governments, finance capital, or mafias, the illegibility of such environments makes it difficult for any single actor to confidently assess the implications of their “moves” in relationship to it.

This production of the unintelligible has never been an absolute guarantee against debilitating interventions. Yet, across many cities of the world, it offers a kind of immunization, a space and a time in which to rethink a range of possible futures; to build upon the resourcefulness potentially immanent in the wide ranging interactions of diverse people and materials within them, as well as to rework the relationships of these spaces with a larger domain of transactions across unruly worlds. As such, the supposed progressive disappearance of a people and terrain already “missing” remains something disturbing, not easily accounted for. To understand what is going on, then, requires new kinds of engagements, not simply a new commitment to go out into this field equipped with the familiar discourses and methodological tools.

The Ruse of Urban Knowledge

For in part, the seeming unintelligibility of these districts is a product of the very proficiency of the methodological tools at our disposal. The intensely urbanized composition of our knowledge about urban matters means that every element and process within cities can be widely articulated across sectors, scales, temporalities, and epistemologies. Whatever transpires on a local level can justifiably have its antecedents in a vast plurality of causes and its implications ramify unbounded across discordant spaces. In the current moment’s renewed fascination with Lefebvre’s notion of planetary urbanization, the city no longer embodies or even is a relevant construct for processes of urbanization. Driven by the exigencies of capital accumulation and the oscillation of making, undoing, and remaking of articulations across spaces, their diverging and converging, urbanization is a process that draws in everything to uses, values, and effects that cannot be necessarily foreseen or negotiated.

As such, planetary urbanization becomes what Timothy Morton calls a “hyperobject,” like climate change or nuclear radiation, something so “big” and omnipresent that the very knowledge that was deployed to “discover” it no longer has any adequacy in terms of navigating a relationship to it. (Timothy Morton,Ecological Thought. Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 2010).

Since hyperobjects “stick” to us like some viscous enwrapping, there is no possibility of analytical distance that would enable us to frame a delimited domain of consideration. And thus, there is no capacity to specify any particular trajectory of where things are headed, only the inter-meshing of ascendancy and decline, consolidation and dissipation. Perhaps more precisely, like climate change, we can formulate that the impact of aggregate actions has implications far outlasting our ability to track them; any particular local manifestation of a hyperobject does not crystalize its essence at any moment, but only points to an implicate order, a “now you see it, now you don’t” simultaneity.

If such is the outcome of an expansive knowledge of urban matters, then it has also been not dissimilarly the phenomena at work in the history of the central city districts I am engaging here. For here, too, there has been the prolific ambiguity as to whether particular households and neighborhoods are “getting better or worse,” where built environments exude an intense proximity of varying states of development and material conditions; where so many modalities of organization (or their lack) are at work that it is difficult to ascertain whether or not households, neighbors, or associations share common agendas or aspirations. In configuring realities not easily disentangled by available analytical tools yet themselves the products of a highly urbanized knowledge, residents ensured the availability of a density of different materials to work with to attain particular, defined objectives. But more importantly, they intersected these materials in ways that they could not have planned or foreseen but that both constrained and opened up other possibilities that could be productively inhabited as a way to continuously adjust to the vagaries of the city.

The inversion of risk and the people to come

A persistent cat and mouse game of an unfinished coloniality may drive “majority” districts of cities to the cultivation and deployment of an intensely urbanized knowledge—where everything that exists within a district might go a lot of different ways, head toward a lot of different futures, just as residents have exhibited a willingness to discover and act on unfamiliar versions of themselves. This process is shaped by a sense of risk, but risk cultivated as an indifference to either the assets that are “put in play” or the specific features of an “outcome.” Residents took risks in part because they knew that to survive they could not stay still. City life was too uncertain, yet the very risk-taking activities of residents contributed to the very volatility that they were hedging against.

Anna Stanley’s (2012) important work on the relationship between risk and capital accumulation rightly emphasizes that risk is not about danger or untoward events and vulnerabilities (Anna Stanley, “Natures of risk: Capital, rule, and the production of difference.” Geoforum 2012. doi:10.1016/geoforum.2012.06.010 ) Rather, it is a means of naturalizing distinctions. In other words, it explains and justifies why certain populations—the most vulnerable and insecure—must disproportionately absorb the deleterious effects of capitalist production. Risk indicates that morbidity, ill health, impoverishment, and accidents are the result of contingency, and that contingency is only available through a language of statistical calculation that discerns patterns and trends in an assemblage of aggregate data removed from contextual specificity. Risk then becomes knowledge critical to practices of governance in that it renders visible the actions of populations in a field of chance. Here differences among people and situations are instrumentalized and abstracted from the ways in which they are produced by economy and politics. Such instrumentalization then permits accumulation to proceed without having to take into consideration the vast range of negative impacts it induces, or, more significantly, as illustrating the overall conditions which only capitalist production is, in the long run, capable of rectifying.

Dillon and Lobo-Guerro also reflect on the relationship between biopolitics and freedom. They rightly point out that the increased emphasis on the molecularization of life and the mechanisms through which various forms of life emerge is not interested so much in the truth of life, of where it comes from, of what it is essentially. Rather, the interest is in finding ways to control the morphogenetic process itself in order to generate “living material” regardless of form. Just as the city was the machine that at its heart was less interested in specifying what inhabitants would become than in struggles over who could control the processes of becoming, freedom, according to Dillon and Lobo-Guerro, is the guarantor of life becoming anything at all (Michael Dillon and Luis Lobo-Guerrero, “The Biopolitical Imaginary of Species-Being,”Theory, Culture & Society (2009), 26: 1–26).

Yet, this notion of risk can be inverted into a position whereby risk points to a capacity to render formerly relied upon social relationships—relied upon to provide anchorage and exposition to everyday life—contingent, i.e. as not necessarily what they have to be.

Drawing upon a philosophical example from Quentin Meillassoux (2011), rather than seeing development as the change of one consistent reality to another, time offers the opening of the possibility that something can end up being what it is, and perhaps anything, for no reason at all. In order for something to be, and to be as it is, there may be necessary properties, but these properties, as Meillassoux puts it, are the consequences of the contingent character of that being—the fact that there need not be a specific reason for why something exists as it does (Quentin Meillassoux, “The Contingency of the Laws of Nature”:Environment and Planning D: Society and Space (2011), 30: 322-334). Because something is constituted in a particular way and at a particular moment suggests that not everything was possible (leading up to that moment), that certain processes and elements converged to limit just exactly what an entity could be and do. But, at the same time, that this something came into existence in the way that it did does not suggest any overarching reason for it doing so. If this is then the case, the particular configuration of relationships inhabited by residents do not necessarily have to be the ones on which they must stake the future survival of their households.

Instead of risk being the language of contingency that obscures the processes through which a household reality has been constructed—a language that abstracts that experience in terms of particular appearances in statistical calculations—contingency becomes a means of “freeing” up livelihoods from a limiting commitment to specific modalities of self-recognition. Residents could get on with negotiating complicated interactions with different facets of the city without necessarily being hindered by the defense of “ultimate bottom lines” or “territories of belonging,” or by taking on cascading social obligations which limited the kinds of perspectives and information residents had available.

Viable, if often limited, livelihoods derived largely from a multiplicity of incremental maneuvers undertaken to build upon and extend whatever a household had access to. These maneuvers often relied upon positioning whatever assets the family had—financial, social, or psychological—within new “neighborhoods” of association. As such, households would speculate on the very conditions that consolidated them as a social unit. In other words, speculative activities put into play the very conditions through which households recognized themselves as a life shared together—i.e. a sense of predictable bonds, shared assets, common collective performances.

For new initiatives often operated against the grain of what the household was accustomed to. They would have to signal their willingness to participate in schemes and with actors that they otherwise might have shied away from; they would demonstrate their willingness to perform roles with others that might be discordant with the way they performed their relationships with each other. Instead of the wider neighborhood being an extension of household ethos, it was actively cultivated as a divergent arena of interests and operations, even when ties of belonging through ethnicity, common place of origin, or religious practice were maintained. Households knew that they operated in a crowded field of various initiatives and that the best laid plans would probably require continuous revisions and adaptation to those of others in order to accomplish anything. Through this, many opportunities for work, improvement of living conditions, and insurance against various volatilities of urban life were secured. But as with all experimentation, there were inevitable fallouts and failures, some of which could not be compensated for, smoothed over, or forgotten.

These reflections are not offered to counteract those of Foucault and Stanley, but rather to indicate a dynamic politics of ruse and dissimulation at work in the relationships between districts of a “nebulous majority,” forms of urban rule converging around the variegated technologies of neoliberalism, and urban analysis and policy formation in general. The supposedly counter-intuitive practices of residents, purportedly operating against their own long-term consolidation and thus interests, opens up considerations of a more complicated, if still unequal and limited, interchange of actions. We can see these as the differentials between actions from “above and below,” “global and local,” “municipal and parochial,” with always the “majority” denied the powers potentially incumbent in this status. But such a hierarchy doesn’t quite get to what is going on. The limitations in what these districts say to urban transformation in general are clear; we can find just so many ways of qualifying and dismissing them. But they still exert a kind of “thereness” whose value and potentials are not clear, and thus not clearly finished. The experiences of these districts cannot be “averaged in” to more generalized formulations. Districts seemingly inoculated against the onslaught of mega-development come to a resounding end; others who wear their vulnerabilities on their sleeves inexplicably hang on, even revitalize themselves.

Deleuze characterizes contemporary cinema as that in which “the people are missing.” For talking about people as being parts of a social class or ethnic identity or political aspiration is not adequate to either the potentials opened up by cinematic events nor the unfolding politics of urban life. As such, the people—the people of the city—have to be invented. This, as the Filipino critical theorist Vincente Rafael puts it, is a different kind of state of exception, perhaps akin to a miracle. Writing about Filipino vernacular experiences of freedom, the missing people discover themselves in the very inviting and welcoming of their arrival in a process that is never completed and is always underway. In other words, the urban majority discovers itself not in dissecting its practices and identities, not at the ballot box, but by always taking on the challenge of paying attention to and absorbing ways of life that are not always recognizable, of creating urban spaces where nothing is summed up, where residents can try lots of different things without feeling like they are going to mess up the situation for everyone. People come together and discover each other, not because they had to, not because they were fulfilling their responsibilities as citizens, but because the opportunity arose in the midst of people doing other things. They may have been dealing with a broken water pipe, strolling leisurely in the streets at night, celebrating a religious festivity that brought together different crowds, gathering around a traveling food cart in a neighborhood, or having a heated yet friendly discussion on public transportation.

The sense of urgency about dealing with the uncertainties of urban life today means that one cannot simply depend upon the inherited notions about people of the past: the old stories about modernity, development and progress. There must be a way of seeing between the lines, or ways of making lines between stories that are going in way too many different directions.

On the one hand, there is enough evidence to be convinced that city life everywhere is heading in a more unified direction. But with such evidence, it is all the more striking that minor differences among places and people can be so powerful and inequities so pronounced. Poverty is being successfully addressed and ignored; well-being is increasing, as is the intensification of dissatisfaction and alarm. Let’s look at all of the containers through which urban life is enacted. There are images of people as objects of class position, cultural, national and religious identity, expressions of probabilistic behavior, risk and development “careers” and indicators of complex configurations of demographic, biochemical and biopolitical variables. Yet they are all inadequate ways of thinking, feelings and speaking about how urban life is experienced and acted upon. The challenge is how to think about lines of commonality, conveyance, and intensity among different facets of urban life that on the surface don’t seem to go together at all.

Photo: São Paulo, Brazil. Credit: Tuca Vieira